Radiant Wound Essai #2: How Journalism Helped Me Write My Poetry Collection

"These convergences created a poetry collection that, I hope, maintains journalistic integrity while exploring emotional truths that traditional reporting alone can't reach."

Welcome to Archipel, an ongoing dialogue between me (Cara Waterfall) and other poets and creatives of all kinds, celebrating the ways we connect through mentorship, community and transitions. If you are interested in participating, please send me an email by replying to this newsletter or click here.

Archipel was inspired by my very first poetry mentor, my father. When you purchase a subscription to this newsletter, you are paying into a scholarship fund in his name, which will support emerging poets.

I’m proud to tell you that the fund currently has $2, 313.32 USD! And we will be raising funds until September 1, 2025, which means we have another seven months before we award this fund to a deserving, emerging poet.

To learn more about The Donald E. Waterfall Scholarship Fund, click here.

Archipel (the French word for archipelago) embodies the idea of being separate yet interconnected. As a French-speaking Anglophone living in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire for the third time with a French partner and three children whose mother tongue is French, Archipel also explores my own experiences with the French language as well as the ways in which poetic language straddles the porous border between the real and the speculative.

Introducing: Essais on Radiant Wound

Archipel will also include occasional reflections on transitions in my life, including my foray into new creative projects, including my Essais on Radiant Wound.

In this series of essays, I explore how my debut poetry collection Radiant Wound (Unsolicited Press, May 20, 2025) emerged from my experiences in Côte d'Ivoire. At its heart, this collection seeks to expand conversations around identity, belonging and the complexities of living between cultures. The French word “essai” means “trial” or “attempt” — a fitting description for reflections on writing poetry as an outsider.

Every poet's journey to publication is vastly different. I began writing these poems while studying at SFU’s The Writer's Studio in 2016. Through many iterations and the thoughtful feedback of diverse readers, the manuscript evolved into its final form. Ultimately, this poetry collection is a love letter to Côte d'Ivoire. I hope it serves as both a bridge and a mirror, illuminating paths across and between cultures.

The catalyst for my debut poetry collection, Radiant Wound, was a grant I received in 2012 from the Glimpse Correspondents program, funded by Matador Network and the National Geographic Society, to produce two long-form features on Côte d’Ivoire: “Rebelles: Ivoirian Women Fight for Change” and “Art as Reconciliation”. I was thankful for the grant, because it gave structure to a chaotic year: it was my first year living in Abidjan and the first time I was freelancing as a journalist and blogger.

I also loved that I would be able to do a deep dive on these subjects, and that I would be working on the editorial process with a seasoned professional. In my case, it was gifted writer and author Sarah Menkedick (check out her Substack, Terms of Endearment).

Sarah was an integral part of bringing these features to life, helping me refine my ideas and craft multiple interviews into a compelling story, which would ultimately help me with my debut poetry collection. A significant number of the poems in Radiant Wound are anchored in these stories and encounters.

Rebelles: First Drafts

I have a post-graduate diploma in journalism from the London School of Journalism, but there is no substitute for experience gathered through firsthand observations and meeting people face to face.

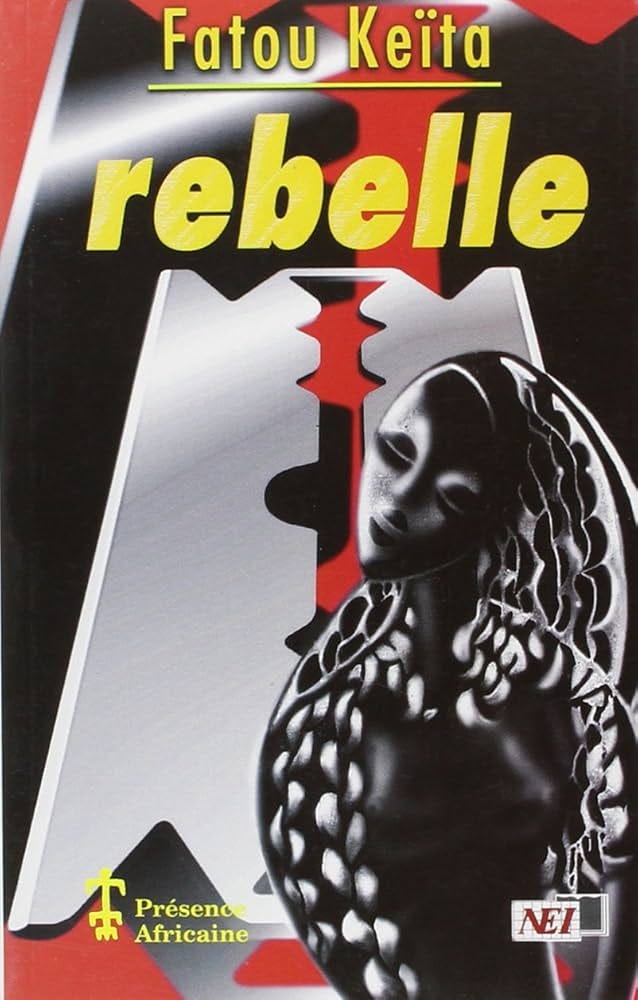

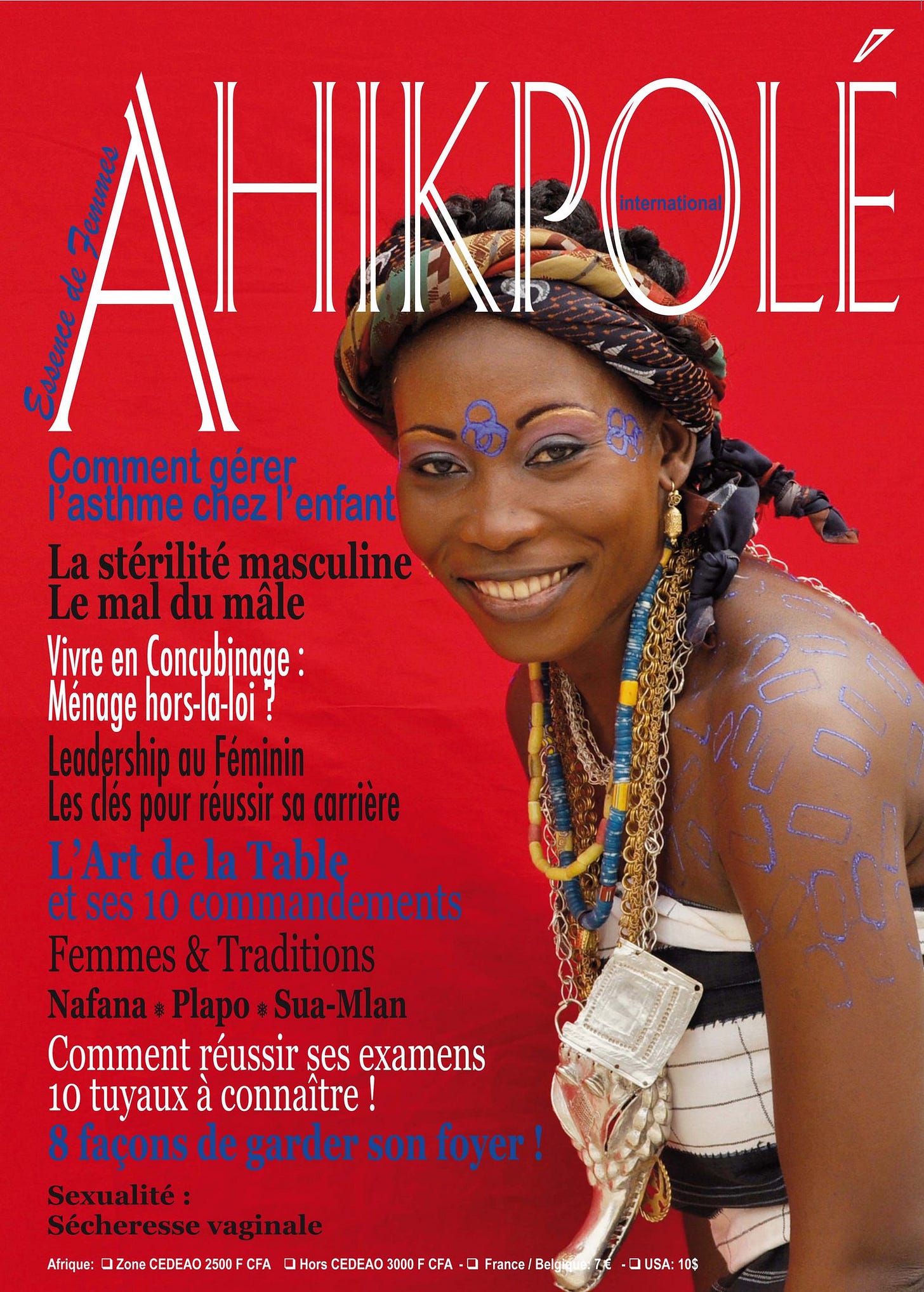

I conducted in-depth interviews with several women, including author Fatou Keita, who I owe a debt to for inspiring the title of my feature, magazine editor and activist De Chantal Ahikpolé and the women working at Amepouh, an organization that supports HIV-positive women and children. These interviews allowed me to weave multiple narrative threads together — female circumcision, domestic violence awareness, HIV/AIDS support — to forge a comprehensive picture of Ivoirian women's struggles and resistance.

I supported the personal stories I had gathered from my interview subjects with data, specifically statistics and information from reports by organizations, like Human Rights Watch and the United Nations.

Refining “Rebelles”: Lessons from Editorial Feedback

In order to arrive at the final draft, I employed a combination of immersive reporting, multiple perspectives and extensive research to create a narrative that honoured the complexity of Ivoirian women's experiences.

Sarah's guidance was invaluable in transforming my long-form feature from fact-heavy reporting into a cohesive narrative. Together, we narrowed the focus to the modern Ivoirian woman, creating a framework that allowed for nuance. Her feedback on my early drafts of "Rebelles" was transformative, highlighting the main areas for improvement, including my tendency toward broad ideas, "poetic abstraction” and relying too heavily on my interview material, while lacking concrete exposition.

Perhaps, the most important advice Sarah gave me, among many valuable insights, was to have confidence in myself “as a shaper and manipulator of the material”: a skill that would prove essential when I was crafting the imagery and layered perspectives in Radiant Wound.

Where Journalism and Poetry Converge in Radiant Wound

My background in journalism and poetry merged in several powerful ways when I wrote Radiant Wound:

The Power of Observation

In journalism, I learned to notice telling details — the "twisted coils of gold rope" adorning a fisherwoman's neck for a magazine cover shoot or the objects in author Fatou Keita’s office, like the grainy photos of ex-combatants injured in the 2011 civil war. This precision allowed me to create evocative imagery in my poems, grounding them in the real world. And evoking all five senses is integral to helping your readers experience other worlds.

Authentic Human Connection

My interviews with women like De Chantal Ahikpolé and the staff at Amepouh taught me to listen carefully and honour the complexity of my interview subjects, whose personal struggles reflected broader social realities, without reducing them to stereotypes, symbols or statistics. This approach directly influenced my poem “Ode to Second Mothers” about Amepouh, where I strived to capture individual voices while acknowledging their place in larger social narratives.

Precision in Language

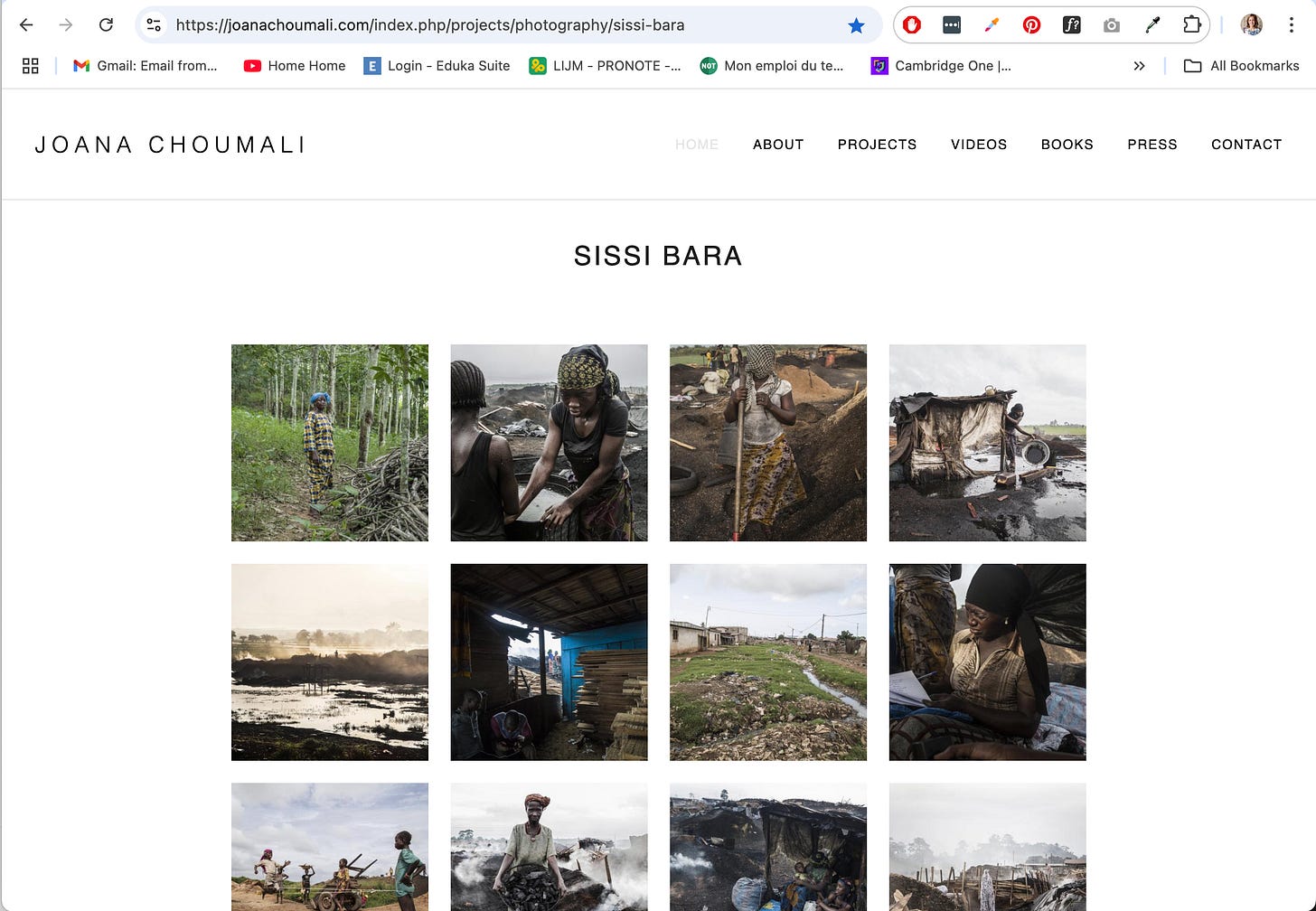

I learned to be careful about the words I chose in order to communicate post-conflict trauma and other difficult concepts with respect. In my poem “Sissi barra: the way of smoke”, inspired by Joana Choumali’s otherworldly photography, I chose words to affirm both the physical labour and human dignity of the charcoal gatherers, avoiding sensationalism while still conveying the weight of their experiences.

Research as A Poetic Foundation

Research details and historical context were my anchors, allowing me to stay connected to my lived experience rather than abstraction. When I wrote about the Fanicos (or laundrymen) at Gbanbgo River, I visited the area and had a guide, who explained the laundrymen were, the process of washing the clothes and what their work days looked like.

I wanted to focus on the individual stories of the Fanicos, who were mostly migrating peoples from Mali and other neighbouring countries. I’m so glad that I was able to document their stories, because they have since been displaced.

Editorial Ruthlessness

Sarah Menkedick's feedback on my “poetic abstractions” taught me to be less self-indulgent in my writing, ensuring that every metaphor, image and word had truly earned its place on the page. This disciplined approach helped me capture authentic voices across Abidjan's diverse communes, like Treichville, Cocody, Le Plateau and Yopougon. This approach was particularly important when I was handling sensitive stories, so that I could avoid mythologizing real people while still maintaining the emotional depth of their experiences.

When Stories Find You

Journalism taught me that powerful stories can appear when you least expect them. For example, the genesis of the poems “Le Président” and “The Crocodile Feeder” (published in The Learned Pig) was an article I had read about the Malian caretaker of the crocodiles, Dicko Toki, who ended up falling victim to one of the crocodiles.

I was struck by several dichotomies. At the time, Côte d'Ivoire was one of Africa's most modern countries and yet Président Houphouet-Boigny was also a chief of one of the Baoulé tribes living in a palace protected by crocodiles that were offered sacrifices. Then there was the stark contrast between Dicko Toki's circumstances and those of President Félix Houphouët-Boigny: the President lived in an enormous palace, while Dicko Toki could only afford a one-story house despite over four decades of faithful service.

Many of my unexpected encounters illustrate this dichotomy between power and marginalization in Ivoirian society, from a chance encounter with a young girl at a traffic light to the young mother playing with her baby at Amepouh’s shelter. These convergences created a poetry collection that, I hope, maintains journalistic integrity while exploring emotional truths that traditional reporting alone can’t reach. I hope that Radiant Wound can stand at the intersection of verified fact and poetic truth.

Journalism and Poetry as Forms of Resistance

One of the objectives of “Rebelles” was to challenge established narratives by using a polyphony of voices and languages, rather than defaulting to a single Western perspective. The research I had done helped me bring nuance to complicated stories, which served me well in the poems I wrote about the women who gather charcoal in San Pedro (”Sissi barra: the way of smoke”) and about Amepouh (”Ode to Second Mothers”).

I also wanted to emphasize how powerful Ivoirian women are, without mythologizing them. When you present people as larger than life, you rob them of their selfhood, flaws and all. It also perpetuates a Western gaze and colonial perspective when applied to people from different cultures. All of this undermines the integrity of the storytelling.

By positioning myself as a witness and outsider — which I talked about in Essai #1: The Poetics of Place — I tried to maintain that delicate balance between immersion and perspective in my poems to create a map that encompassed both the tangible and intangible aspects of Côte d’Ivoire. I hope that the end result is a book that allows for a form of respectful resistance against oversimplified narratives about identity, culture and place.

Embracing Discomfort

When I was in Banff in January, the inimitable poet Danez Smith said that people don’t like to feel negative emotions anymore. Maybe the most important aspect of doing these interviews was embracing discomfort to reach a deeper understanding about the people I was interviewing — and about myself. Every error and detour helped me grapple with the challenges of representation and the ethics of storytelling.

Two Ways of Seeing

I love that two forms of storytelling can strengthen one another. The rigorous research and ethical considerations I learned through journalism helped provide the foundation for my poetry, while poetry offered me the freedom to explore emotional truths in a way that journalism could not capture. Through this synthesis, Radiant Wound pays testament to the power of careful observation and mindful presence.

As always, thank you for reading!

With love and intention,

Cara

Cara, thank you for another fine (radiant) essay. I understand better why your poetry is powerful: your depth of research, your ability to form intimate connections with your subjects, and then your capacity to find the perfect expressive distance, so letting your subjects speak for themselves. Among your many talents, you are an educator.