Radiant Wound Essai #1: The Poetics of Place

"...writing about life overseas is a fragile equilibrium between immersion and perspective."

Welcome to Archipel, an ongoing dialogue between me (Cara Waterfall) and other poets and creatives of all kinds, celebrating the ways we connect through mentorship, community and transitions. If you are interested in participating, please send me an email by replying to this newsletter or click here.

Archipel was inspired by my very first poetry mentor, my father. When you purchase a subscription to this newsletter, you are paying into a scholarship fund in his name, which will support emerging poets.

I’m proud to tell you that the fund currently has $2, 313.32 USD! And we will be raising funds until September 1, 2025, which means we have another seven months before we award this fund to a deserving, emerging poet.

To learn more about The Donald E. Waterfall Scholarship Fund, click here.

Archipel (the French word for archipelago) embodies the idea of being separate yet interconnected. As a French-speaking Anglophone living in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire for the third time with a French partner and three children whose mother tongue is French, Archipel also explores my own experiences with the French language as well as the ways in which poetic language straddles the porous border between the real and the speculative.

Introducing: Essais on Radiant Wound

Archipel will also include occasional reflections on transitions in my life, including my foray into new creative projects, including my Essais on Radiant Wound.

In this series of essays, I explore how my debut poetry collection Radiant Wound (Unsolicited Press, May 2025) emerged from my experiences in Côte d'Ivoire. At its heart, this collection seeks to expand conversations around identity, belonging and the complexities of living between cultures. The French word “essai” means “trial” or “attempt” — a fitting description for these reflections on writing poetry as an outsider.

Every poet's journey to publication is vastly different. I began writing these poems while studying at The Writer's Studio in 2016. Through many iterations and the thoughtful feedback of diverse readers, the manuscript evolved into its final form. Ultimately, this poetry collection is a love letter to Côte d'Ivoire. I hope it serves as both a bridge and a mirror, illuminating paths across and between cultures.

The Challenge of Writing Place

Radiant Wound emerged from my desire to make sense of my out-of-placeness and to capture my lived experience as it was happening in 2012, shortly after the Second Ivorian Civil War. My relationship with Abidjan evolved over each return: first as a freelance writer with my partner, then with two sons in 2019 and finally in 2023 as a mother of three. Each time, the city and I had changed.

Writing poetry about a foreign place requires a delicate balance of observation, empathy and self-awareness. As a cultural and linguistic outsider, I have to navigate both physical and personal geographies. In order to bring the physical landscapes of Radiant Wound to life, I used sensory details and map specific locations, from the presidential palace in Yamoussoukro to the colonial ruins of Grand Bassam and more intimate spaces, like a woodcarver's studio and the Gbangbo River.

The intersection of these geographies enabled me to capture the physical reality of Côte d'Ivoire and the emotional landscape of living between cultures. In the end, I hope that I have created a poetic map that encompasses both the tangible and intangible aspects of a place.

The Outsider's Lens

As an expatriate — defined as a person living outside of their native country — writing about life overseas is a fragile equilibrium between immersion and perspective.

While I may have gained some insights about my adopted country, I never presume to have authority over experiences that aren't wholly my own.

As time passes in a foreign place, you become more comfortable, but as a writer, you have to resist complacency. You can never claim full comprehension over the country and culture you are inhabiting. I am always aware of my limitations as an outsider, even while my connections here may deepen.

Being an expatriate comes with privilege. My partner and I have chosen to live in Abidjan three times. We have the privilege of choice in our relationship to place: the ability to arrive and depart at will — a freedom that is not available to everyone.

An expatriate's relationship with their adopted home is often finite. I feel a sense of urgency and bittersweetness in my observations and interactions, knowing that we won't be here forever. In this way, a chosen country is very much like chosen family: it is about deliberate engagement and a profound emotional investment.

The challenge lies in honouring both the depth of my connections and the inherent transience of being an expatriate poet, while creating work that acknowledges this sense of belonging and distance.

Position and Perspective

"The lyric "I" that emerges from the Western canon through to a critique that emerges from within the Western canon is still of a piece; so the aggregate, con-ceptual "we" is Western too, like it or not. Put another way, if anyone is ethnic, everyone is ethnic. There is no poetry as such, and this can only be appreciated if one acknowledges who one reads, who one values, and who one's writing and scholarship responds to, over and above whatever smattering of tokens one might find one one's bookshelf. Could there be a universalist poet or critic? Only if one had several lifetimes to study and become expert in all the traditions there are. Given that's impossible: do the next best thing: let the fallacy of universalism in literature go."

~ Wayde Compton, Toward an Anti-Racist Poetics

Wayde Compton argues that writers must acknowledge their specific cultural position, rather than assuming a universal voice. In Radiant Wound, I aligned my poetry with Compton's anti-racist framework by positioning myself as a geographical, cultural and linguistic outsider first, and wrote through a postcolonial lens while grounding my observations in specific locations and experiences.

Language and power dynamics are crucial to Radiant Wound's engagement with anti-racist poetics. Rather than defaulting to a Western perspective, I employed a polyphonic approach, incorporating various languages and voices from the Ivoirian community rather than claiming a single perspective. This multilingual engagement was both an aesthetic choice and a political statement — to recognize the power structures inherent in language choice.

A Few Guidelines for Writing about a Foreign Place

I've gathered a few guidelines on writing poetry about a foreign place that have proven helpful to me. (I'll be writing in more detail about some of these guidelines in later essays.)

Acknowledge where you are writing from.

As I discussed previously, a good rule of thumb is to begin by acknowledging your position in relation to that place. Places and people change, as do our memories and perceptions of them. It's important to continually evaluate and re-evaluate what you have written and where you are writing from.

Research and read extensively.

Study the history, culture and current affairs of the place you are living in to provide context and depth. Read extensively, whether it is local literature, news articles or blogs. Educating yourself is a form of respect that will hopefully help you avoid stereotypes and write with greater sensitivity.

Face-to-face connections are vital.

Meeting people in person allows for a greater engagement on every level, including a sensory one, and is essential to building trust in a relationship.

Embrace specificity.

Paying close attention to every aspect of your environment is essential to bringing a foreign place to life. By incorporating all five senses into your writing and describing your surroundings in great detail, you can help the reader enter the world you are building.

Embrace nuance.

To add nuance to your poetry, use figurative language, like metaphor, allusion and anaphora, among other devices, to produce subtle variations in tone, mood and expression.

Acknowledge what you can't fully grasp about a place.

You don't know what you don't know. Having humility — and being true to the observation of a particular moment — can make your writing more honest.

Understand why your work matters to you.

At the Winter Writer's Residency I attended in Banff this January, I asked writer and journalist Omar El Akkad how I could ensure I was being ethically responsible when writing about the Ivoirians and Côte d'Ivoire. How could I make sure that I was showing my appreciation for this country without appropriating its culture?

He said that people will always be critical of your work. And some of those criticisms may be valid, in which case your job is to listen and learn from your mistakes. But other criticisms may be less valid, which is why it's important to understand the underlying reasons why your work matters to you — or matters at all — so they can act as an anchor when people are questioning your creative work. I like to think of these reasons as a grounding force, rather than a defensive act.

No writer can be all things to all people. When I write poems as an outsider, I am not striving for universalism, but I am trying to capture something authentically human in the space between cultures and language.

A Poetic Geography

People often talk about world-building in fiction, but I love the idea of world-building in poetry. In Radiant Wound, I tried to evoke the rich and multi-faceted world of post-civil war Côte d'Ivoire by layering poetic techniques and perspectives to capture the complexity of a nation in healing.

The world-building begins with vivid geographical mapping, taking readers from the crocodile-guarded presidential palace in Yamoussoukro to the colonial ruins of Grand Bassam, and into more intimate spaces like a woodcarver's studio and the Gbangbo River. These places serve as anchors for a deeper exploration of cultural and emotional territories.

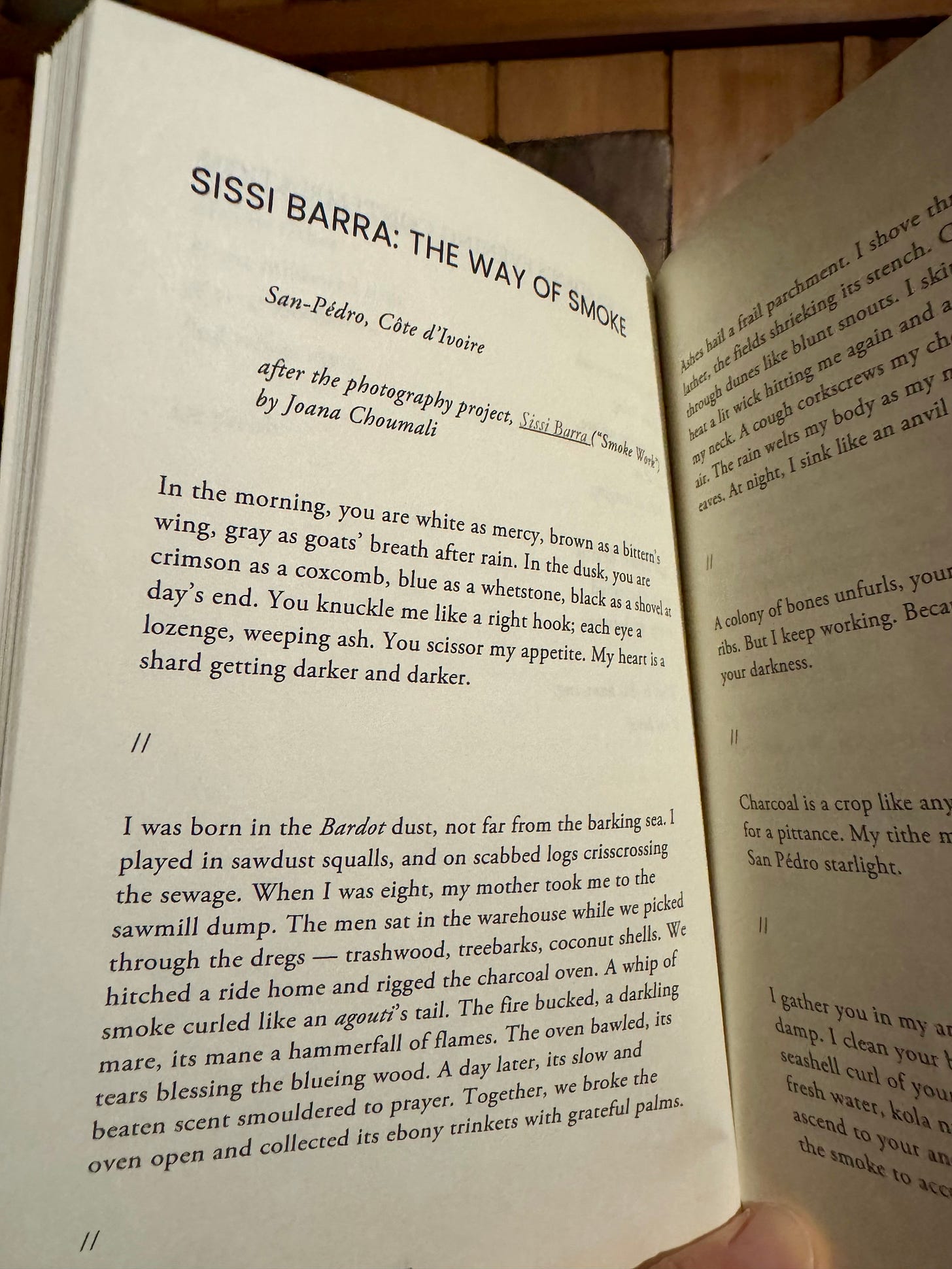

I tried to engage a polyphony of unheard voices, like the young girl making charcoal in San Pedro, HIV-positive women and vulnerable children in Yopougon, and even the neglected animals of the Abidjan Zoo — each with their own perspectives on survival, tradition and resilience.

Language was also a tool for my world building, as my poems oscillated between cultures and tongues. This multilingual approach reflected the complex cultural dialogues taking place in post-conflict Côte d'Ivoire, and also mirrored, in microcosm, my own struggle with living between many languages.

In 2011, I received a National Geographic Glimpse Correspondent grant to produce two long-form features on Côte d'Ivoire: “Rebelles: Ivoirian Women Fight for Change” and “Art as Reconciliation”. These interviews and my personal experiences helped me create a poetic landscape that I hope bears witness to both wounds and healing, and provided a space where personal and collective histories might intersect.

Final Thoughts

Can an outsider strive for authenticity? Absolutely. Will it be reflected on the page? Not always. What may be true is that you have written authentically through the lens of your own experience.

If you remain respectful, humble and steer clear of cliches, stereotypes, exoticism — and all the other pitfalls of mediocre or poor writing — you may have an opportunity to expand the perspectives of people who engage with your creative work. For me, that’s reason enough to keep on writing.

As always, thank you for reading!

With love and intention,

Cara

I'm really looking forward to reading your book.