#7: An Interview with Kim Fahner

"By working together, whether through mentorship, or through volunteering to help build community, we make our writerly community in Canada stronger and more tightly woven."

Welcome to Archipel, an ongoing dialogue between me (Cara Waterfall) and other poets and creatives of all kinds, celebrating the ways we connect through mentorship, community and transitions.

If you are interested in participating, please send me an email by replying to this newsletter or click here.

Archipel was also inspired by my very first poetry mentor, my Dad. When you purchase a subscription to this newsletter, you are paying into a scholarship fund in his name, which will support emerging poets.

To learn more about The Donald E. Waterfall Scholarship Fund, click here.

Thank you for reading!

Today's interview is with Canadian poet and writer, Kim Fahner. She is the First Vice-Chair of The Writers' Union of Canada (2023-25), a full member of the League of Canadian Poets, and a supporting member of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. From 2016-18, she was also Poet Laureate for the City of Greater Sudbury. Kim also finds time to be a high school teacher, while advocating for emerging poets and writers across ages, genres and communities. As a fierce champion of Canadian literature, she is a builder of communities and a firm believer in paying it forward when it comes to mentorship.

Kim is the author of several books of poetry, including The Narcoleptic Madonna (Penumbra Press, 2012) and Emptying the Ocean (Frontenac House, 2022). Her sixth poetry collection, The Pollination Field is forthcoming form Turnstone Press in Spring 2025.

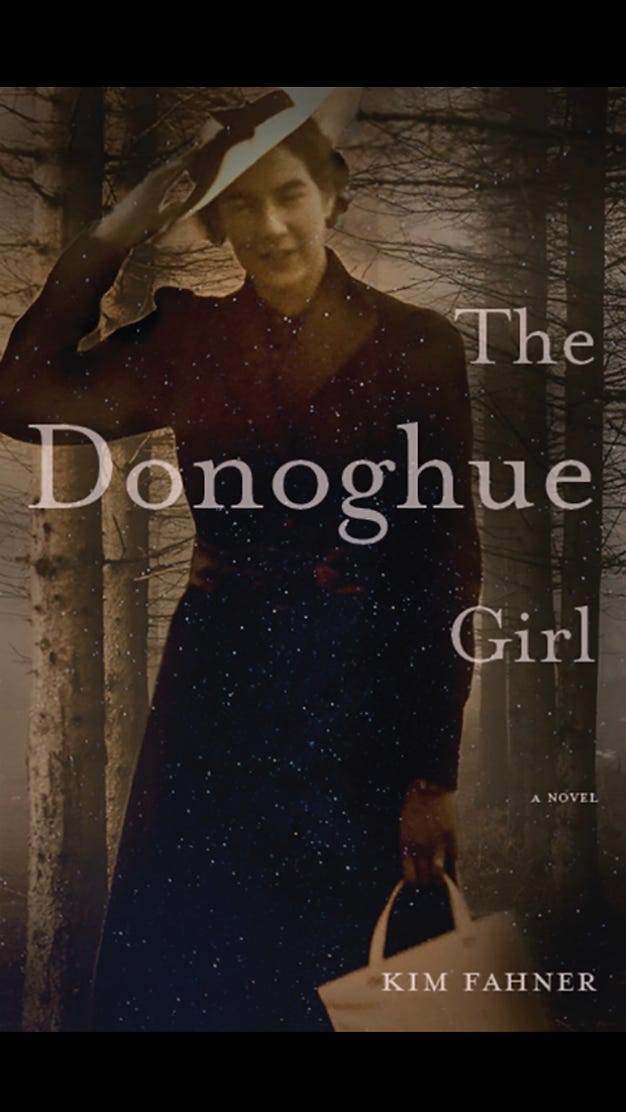

Her first foray into fiction is the novel, The Donoghue Girl (from Latitude 46 Publishing, 2024) in which she deftly explores the trials and tribulations of Lizzie Donoghue, the daughter of Irish immigrants living in a Northern Ontario mining town in the 1920s and ‘30s. The story was inspired by Kim’s family history as well as the Northern Ontario landscape that she knows so well as a native Sudburian.

The Donoghue Girl is available for order now: https://store.latitude46publishing.com/products/sisus-winter-war-copy

Who are you and how do you express your creativity or describe your art?

I’m a writer and teacher. I’ve always been creative. From a young age, I was reading books voraciously and then making up stories in my head. My mum always said I had a big imagination, so I guess it makes sense that I became a writer. People might mostly know me as a poet as I’ve published five books of poems, but I’ve been writing short prose pieces since I was in my 20s. They just weren’t published.

Now, I write across genres—poetry, drama, creative nonfiction, novels—and I also dabble in visual art. I fell in love with creating letterpress broadsides of poems back in 2018, when I lived in Kingsville (just outside of Windsor) for a year while writing my second novel. I worked with Jodi Green of Levigator Press in Windsor, who taught me how to make those broadsides, and I got hooked on linocut and letterpress printing then. Since 2022, I’ve also experimented with water-colour and free form embroidery, so I am now exploring visual art, as well.

For me, art is creativity—regardless of the medium—and it’s how I move in the world. Most days, art helps me to make sense of a world that doesn’t seem kind or sane, so I’m grateful for its presence in my life.

What keeps you coming back to creative work? Why is it worth doing?

Creative work is what keeps me alive, I often think. For me, writing is like breathing. I can’t imagine not doing it, to be honest. I couldn’t stop being creative, or writing creatively, if I purposely tried to do so. It’s worth being creative, and making art, because it’s something that brings light to a too often dark world. I have always loved that famous Bertolt Brecht quote about singing in the dark times. That quotation speaks to the power of creativity and the human spirit. In times of great worry or pain, we turn to the arts to lift our hearts and minds. We turn to it in times of joy, too, but maybe we value it more when we’re facing great challenges.

There’s value in making art, but there’s value in sharing it, too, and in encouraging others to try and make art if they’re curious about exploring it.

As a teacher of young people, I’m a strong advocate for the arts in our elementary and secondary panels of education. I’ve watched kids stay healthier over the years, in terms of their mental health and well-being, by expressing themselves creatively—whether through visual art, creative writing, music, or drama. Making art is a key part of keeping well and flourishing for so many creative people.

What legacy do you hope to leave with your art?

The word “legacy” has such weight to it that it makes me a bit nervous!

As a teacher, I hope that my legacy is that my students might see that you can have a ‘day job’ and be a professional artist at the same time. The two may not directly mirror one another, but instead make one another richer in depth and texture.

I hope that my focus on teaching young people (through my teaching career since 2001) and in mentoring emerging writers of all ages is my legacy, beyond whatever books I’ve published. I believe veteran writers should offer guidance and mentorship to emerging writers, to help make their way easier than ours was when we were starting out in the field. In my volunteer work with The Writers’ Union of Canada,

I’m really proud of the fact that we are aware of the importance of creating community in our various circles of writers, and we help to build future generations of Canadian writers through creating a supportive and collegial community, fighting copyright law infringement, and through speaking up for the rights of writers in our everyday lives.

What are your biggest challenges when it comes to maintaining a steady creative practice, and how have you overcome them?

I have always struggled to balance my creative writing with my high school teaching job. It means getting up early each day—around 5am—and putting aside a chunk of time to read and write. As someone who has mostly taught English over the last two decades, it’s been trying in terms of finding time to write because of the heavy marking and planning for that subject area, but I’ve managed. At weekends, I try to carve out a full day where I can just focus on my creative work.

I’m also aware, though, that my work as an educator does wear me down energetically, so I know that sometimes I need to just rest. Still, I’ve never been one to sit still, so I’m usually always working away at something literary, even if it’s reading a poetry book to prepare for writing a review, or mentoring an emerging writer in a meeting to talk about their poems.

I have always purposefully carved out time for my creative work. The world won’t put aside that time for artists to create.

As a writer, it’s an often solitary and very focused path, so I tend to mostly have a small circle of fellow writers and artists (actors, singer-songwriters, musicians) as friends just because other people don’t seem to understand the demands of—or the magnetic pull of my attraction and dedication to—my creative work.

What advice do you have for someone who wants to start or maintain their creative practice in a new way?

I like to explore new forms of creativity, and I challenge myself to try new art forms. My recent forays into the visual arts in the last few years, in particular, have brought me a great deal of joy. I think it’s mostly about time, and how we choose to manage it. There will always be someone who wants a bit more of our time and attention, but as creatives and artists, we need to be mindful of its importance to our lives, and we need to establish boundaries to protect that time and energy. People may not understand that need to be focused on our creative work, and they may drift from our lives, but the art remains. I love Chelene Knight’s work around guarding creative energy and making time for writing in your day.

For me, creativity and art have always been the things that have stayed in my life, even while people have departed it. That said, I have learned—especially in the last three years—to cultivate my circle of friends to be mostly creatives. Others just don’t seem to understand the demands of an artist’s call to explore their field, so it’s best to be around like-minded artists.

I think all people are creative, but that some families may not cultivate that spark of creativity, so schools can be places where children can discover their creative gifts.

As adults, I think it’s about going outside of our comfort zones to experiment with new forms of creativity. Being curious can help, and wanting to feel out of our depths can help, too, as it means we’re willing to explore all possibilities.

Taking a workshop in some artistic field can create connection with other creative folks, and can lead you to learn more about your craft, or some other medium.

Why does mentorship/ community support matter?

I didn’t always have a mentor as a young, emerging writer, so I’m perhaps more aware of the importance of mentorship in my early 50s. A mentor can encourage an emerging writer, reassure them that their work is valuable and growing in strength, especially when the voice of any inside critic might be louder than the voice of their inside artist.

I’ve found great joy in working with emerging poets, in particular, over the last four years, consulting with them over their respective works-in-progress—whether via Zoom or in person. These conversations about craft, and about poetic intention and purpose, have been as educational for me as they might have been for my mentees. I’m hopeful that my guidance has been helpful.

Moving between genres as I do, and especially recently as I’ve just released my first novel, The Donoghue Girl, I’m also aware of the importance of finding writing mentors who have expertise and experience in different genres. I began in poetry, and still write it, but writing plays and novels, as well as creative nonfiction essays, is a relatively new shift in my work as a writer. I’m so grateful for those mentors who have guided me into those various genres.

In terms of community, I believe in building relationships. I always have believed in the importance of volunteer work, and I’ve been an active volunteer in Sudbury since my 20s. Now, in my work with The Writers’ Union of Canada (TWUC), I continue to speak of the rewards of volunteerism and non-profit work in a time when that sector is at risk. By working together, whether through mentorship, or through volunteering to help build community, we make our writerly community in Canada stronger and more tightly woven.

Too, I think this is why I love writing poetry book reviews, sharing new books of poetry with a reading audience to support my fellow poets across this country. We’re a small band of poets, but we’re strong and well connected, and I love that about how our community works.

Do you have a mentor?

I actually have a few, but my first writing mentor was Timothy Findley. I worked with him on a series of short stories through the Humber School for Writers back in the mid-late 1990s, and he was very encouraging of my work. I think he saw some worth in my work at the time that I couldn’t see. Now, I am confident in my writing, but then I was completely unsure.

More recent literary mentors include Lawrence Hill, Marnie Woodrow, Matthew Heiti, Catherine Banks, Tanis MacDonald, Ken Babstock, John Glenday, Jen Hadfield, and Susan Rich. These mentors move across genres that I’ve been experimenting in over the years—from poetry, to plays, to creative nonfiction, to novels. They have all been some of my best teachers, and I’m extremely grateful to them for their guidance over the years. A few have become close friends, and for that, I’m even more grateful.

Who is your dream mentor, living or dead, and why?

I have two dream mentors, and it will be no surprise to those who know me well: Seamus Heaney and Mary Oliver.

I met Seamus Heaney once in a Sligo pub and said hello to him, but then could not even find the words to have a conversation, mostly because I was so shocked to have encountered him unexpectedly. I met him in that pub on a summer afternoon in 2012, the year before he died, but I had studied his work since the early 1990s, and my Master’s thesis was on his bog poems as they related to both politics, creativity, and art, so he is the person I consider my poetic father in some strange fashion.

Meeting him that day felt eerily fated, and I’ll never forget it. In terms of Mary Oliver, I came to her work in a yoga class in my early 30s, when my teacher—Willa Paterson—read one of her pieces during savasana. I was hooked and read all her work within a year or so.

I so admire what both Heaney and Oliver do with the natural world, and with how they use language and imagery to describe things that lead me to think more about bigger, philosophical ideas. Their work—both in essays and poetry—is important to me in terms of how I understand the notion of what creativity is, the notion of there being a Muse/inspirational force, and of how that creativity can be channelled into a piece of writing. Their keen knowledge of craft, too, always drew me to their work. Heaney’s essays about the function and power of poetry, especially in The Government of the Tongue, had a significant influence on me as a young poet while I was studying his work intensely in the early 1990s, and I’m fond of Oliver’s prose collection, Upstream, which has more recently intrigued me for similar reasons.

In terms of living mentors who teach me more about poetry, Yvonne Blomer, Micheline Maylor-Kovitz, John Glenday, Jen Hadfield, and Alice Major have been influences on me in terms of turning my focus to look more closely at my poetic craft. I also really love Betsy Warland’s book, Breathing the Page: Reading the Act of Writing for how it’s shifted my head around how poetry works on the page. In terms of prose, Timothy Findley, Lawrence Hill, and Marnie Woodrow have been my most important teachers. And, for play writing, Catherine Banks has been instrumental in helping me to re-see the way my plays work/should work. For creative nonfiction, Tanis MacDonald has been my guide and mentor. I’m grateful to all of them for their teachings and guidance.

(Interview answers received via email October 5, 2024.)